What Is Term Premia?

In bond markets, term premia (or term premium) refers to the extra yield or return that investors demand for holding a long-term bond instead of a series of short-term bonds. In other words, it’s the “premium” investors require to compensate for the risk of locking up their money for a longer period, during which interest rates and inflation could change. For example, if you could invest in a 1-year Treasury repeatedly over ten years, the term premium is the additional yield that a 10-year Treasury must offer to persuade you to hold it for the full decade rather than re-investing each year. Typically, long-term bonds yield more than short-term bonds (a positive term premium) because investors want to be paid for risks like unexpected inflation or interest rate volatility over time. However, term premia can fluctuate and even turn very low or negative if investors are willing to hold long-term bonds at yields equal to or below expected short-term rates – something that has happened in recent years.

Figure: The 10-year term premium has declined dramatically since the 1990s, even turning negative in the late 2010s and early 2020s. (Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York data)

Several factors determine term premia. A key driver is perceived risk: if investors fear higher inflation or economic uncertainty, they will demand a higher term premium (raising long-term yields) to compensate for that risk. Conversely, when long-term inflation fears subside (as they did after the 1980s), investors accept a smaller premium. Another driver is supply and demand for bonds. If there is strong demand for safe long-term Treasuries – for instance, during global political turmoil when investors seek safety, or due to regulatory requirements for banks and pensions to hold safe assets – then long-term yields can be pushed down, reducing term premia. Central bank actions can also play a role: when the Federal Reserve engaged in quantitative easing (buying long-dated bonds), it increased demand for those bonds and thereby lowered term premia by roughly 1.1 percentage points during the post-2008 period. In summary, term premia reflect a mix of investor risk appetite and market technical factors (like bond supply and demand), and they are a crucial component of why long-term interest rates may differ from just the expected path of short-term rates.

Term Premia vs. Credit Risk

Term premia and credit risk are separate concepts. Term premia reflects uncertainty about future rates and inflation, not default risk. However, if investors begin to view U.S. debt as unsustainable, term premia can rise alongside perceived credit risk—blurring the line between market discipline and sovereign risk pricing.

Why Term Premia Matters for Markets and the Economy

Term premia might sound like an abstract finance concept, but it has real and broad impacts on the financial markets and the economy:

· Long-Term Interest Rates & Borrowing Costs: The term premium is a component of long-term interest rates (such as 10-year Treasury yields). A higher term premium leads to higher long-term interest rates for the same expected path of Fed policy, which makes borrowing more expensive for households, businesses, and the government. For example, mortgages, student loans, and corporate bonds often price off the 10-year yield. If term premia rise, those rates rise, increasing the cost of financing homes, investments, or government deficits. Conversely, historically low term premia in recent years helped keep long-term rates low, enabling cheaper loans and refinancing.

· Asset Prices and Long-Term Assets: Term premia affect the valuation of long-term assets like stocks and real estate. Lower term premia (and thus lower long-term yields) mean that future cash flows are discounted at a lower rate, which tends to boost valuations for equities, real estate, and other assets that produce returns over a long horizon. This was one reason stock markets and home prices benefited in the 2010s when term premia were unusually low by historical standards. On the other hand, if term premia increase significantly, all assets valued via discounted cash flows could see lower prices because the discount rate is higher. In a recent analysis, PIMCO noted that a return of term premia to levels seen in the early 2000s (around 2% vs. near 0% recently) “would not only affect bond prices but also prices of equities, real estate, and any other asset valued based on discounted future cash flows”.

· Economic Growth: By influencing interest rates, term premia also influence economic activity. When long-term rates rise due to a higher term premium, financial conditions tighten – loans are pricier and businesses may cut back on investment, potentially slowing growth. Government interest payments also mount. In the United States, after years of low rates, the jump in yields through 2023–2024 meant that total federal interest payments were poised to reach their highest share of GDP in the post-WWII era. A higher debt servicing burden can crowd out other government spending or require higher taxes in the future, creating a drag on the economy. On the flip side, low or falling term premia ease financial conditions and can stimulate growth by making credit cheaper. This dynamic means that changes in term premia can either amplify or counteract the Federal Reserve’s own interest rate moves in steering the economy.

· Market Sentiment and Stability: Term premia also capture a sort of market sentiment about risk. A spike in the term premium often reflects investors demanding more compensation for uncertainty – this can coincide with market volatility and declines in riskier assets. For instance, if investors suddenly worry about fiscal deficits or inflation, they might sell long-term bonds, causing yields to surge (higher term premium). Such an episode can shake other markets; a notable example was in late 2023 when concerns about large government deficits and a credit rating downgrade contributed to rising long-term yields globally. This reminds policymakers that market-driven increases in term premia (“bond vigilantes,” as famously dubbed in the 1980s) can impose discipline on fiscal and monetary authorities by making borrowing more expensive if they stray into unsustainable policies.

In short, term premia are important because they directly influence the level of long-term interest rates beyond what the Fed sets, thereby affecting everything from the cost of a mortgage to the valuation of your 401(k) portfolio. Keeping an eye on term premia helps investors and policymakers gauge whether changes in long-term rates are driven by shifting outlooks for economic fundamentals (growth/inflation) or by changing attitudes towards risk and bond supply.

Term Premia and the Federal Reserve’s Decisions

The Federal Reserve primarily controls short-term interest rates, but it pays close attention to term premia and long-term rates when making policy decisions. One reason is that long-term yields (like the 10-year Treasury rate) feed into borrowing costs across the economy. If long-term rates move significantly due to term premium changes, it can either counteract or reinforce the Fed’s own policy stance. For example, former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan once highlighted a “conundrum” in 2006 when the Fed raised short-term rates but long-term rates barely rose – this was later attributed to an unusually low term premium at the time (due in part to global demand for Treasuries). In that case, the Fed’s tightening had less effect on mortgage and corporate rates because long yields stayed anchored. Conversely, if long-term yields surge while the Fed is holding rates steady, it’s effectively a hidden form of tightening of financial conditions.

The Fed can also influence term premia through its tools. During quantitative easing (QE) programs, the Fed bought trillions of dollars of longer-term Treasury and mortgage bonds, explicitly aiming to lower long-term yields by reducing term premia. The Fed’s own research found that these purchases significantly lowered the term premium on 10-year Treasuries. Even today, the Fed’s ongoing balance sheet strategy (letting bonds run off) and communication about future bond purchases can affect term premia. Additionally, forward guidance – pledges about future short-rate policy – can reduce uncertainty and risk, also tending to lower the term premium if credible.

It’s important to note that the Fed’s rate decisions take term premia into account indirectly via the yield curve. An inverted yield curve (short-term rates above long-term rates) often indicates very low or negative term premia and expectations of future rate cuts. The Fed might be cautious about raising short-term rates too far if long-term rates don’t move, to avoid an excessive inversion that could signal a recession. In the current environment (mid-2025), the yield curve has been inverted with cash (short-term instruments) yielding more than longer-dated bonds. Historically, such inversions often precede recessions. Fed officials are aware that part of this inversion is due to low term premia in recent years. One likely resolution is through Fed rate cuts that bring short rates down (steepening the curve), but another possibility is that term premia themselves could rise (pushing long rates up). This uncertainty makes the Fed’s job trickier – they must balance inflation and employment goals while also watching for any abrupt changes in term premia that could destabilize markets or the economy.

Finally, the Fed’s policy communication and projections reflect assumptions about term premia. The “dot plot” (the Fed’s Summary of Economic Projections for interest rates) implicitly assumes some path for longer-term yields. If Fed officials believe that factors like high public debt or waning global demand for Treasuries will increase term premia going forward, they might expect long-term yields (and perhaps the neutral policy rate) to be higher. Indeed, some Fed members have hinted that persistently large deficits could raise the neutral rate of interest over time. For now, the Fed’s median longer-run forecast for the fed funds rate sits around 3%, but upside risks (like fiscal pressure or inflation expectations) could push that higher if bond investors demand more yield to lend long-term.

Treasury Issuance, QRA, and the Bill-to-Bond Composition

While the Federal Reserve sets short-term interest rates, the U.S. Treasury plays a powerful role in shaping long-term yields and term premia through its debt issuance strategy. As the U.S. runs large deficits—amplified by Trump’s “Big Beautiful Bill”—the Treasury must issue more debt. But how it issues that debt has major implications for duration supply and investor demand.

The Quarterly Refunding Announcement (QRA) updates investors each quarter on the size and maturity structure of Treasury issuance. A short-term-heavy issuance plan helps cap long-term rates, while more issuance in long-dated securities can elevate term premia.

In recent QRAs, the Treasury has leaned on bills to reduce pressure on long-term rates. While this can lower yields temporarily, it creates rollover risk and may raise long-term concerns, potentially increasing future term premia if investors worry about debt sustainability.

This chart shows the trend in Treasury issuance composition and how it correlates with changes in the 10-year yield and term premium. Issuance strategy is becoming a key policy lever as fiscal needs grow and market sensitivity increases.

Liquidity Plumbing: Reverse Repo and Funding Channels

As the Fed unwinds its balance sheet, Reverse Repo (RRP) usage is falling, potentially releasing liquidity back into Treasury markets. This may partially offset term premia pressures by redirecting cash from short-term facilities into longer-dated debt. However, this cushion is finite and subject to broader macro conditions.

Term Premia in Bessent’s “3-3-3” Economic Plan

The concept of term premia even finds its way into fiscal strategy under the current U.S. administration. President Donald Trump’s second-term Treasury Secretary, Scott Bessent, has outlined a “3-3-3 Plan” for the economy. This plan sets three ambitious targets to be achieved by 2028:

1. Budget Deficit of 3% of GDP: Reduce the federal deficit from roughly 6.5% of GDP in 2024 to 3%. This implies major spending cuts or revenue increases to more than halve the deficit as a share of the economy.

2. Real GDP Growth of 3%: Achieve sustained 3% annual economic growth (significantly above recent trend growth of ~1.5–2%). Faster growth would help increase tax revenues and make the debt burden more manageable.

3. Increase Oil Production by 3 Million Barrels/Day: Expand U.S. domestic oil output by 3 million barrels per day (about a 15–25% increase from roughly 12–13 million currently). This is intended to lower oil prices and inflation, keeping energy costs and headline inflation in check.

The overarching goal of the 3-3-3 Plan is to stabilize the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio at about 100% by late this decade. By boosting growth and trimming deficits, while also pushing inflation down via cheaper energy, the plan aims to prevent the national debt from spiraling higher relative to the economy. But how does term premia fit into all of this? It turns out that long-term interest rates – and by extension term premia – are an important piece of the puzzle.

Bessent’s plan explicitly counts on lower medium- and long-term interest rates to save money on interest costs. In fact, analysts note that the plan “factored in considerable savings from a forthcoming decrease in the 10-year bond yield.” In other words, part of how the 3-3-3 targets would be met is if long-term Treasury yields come down, reducing the government’s cost of borrowing on new debt. A “goldilocks” scenario of lower term premia, subdued inflation, and higher growth would ease the debt burden significantly. Lower long-term yields mean the Treasury can refinance debt more cheaply, so even stabilizing debt at 100% of GDP becomes more feasible if the interest rate on that debt is low.

However, there’s a tension here. Achieving a smaller deficit and high growth simultaneously is challenging – deep spending cuts could slow growth, and without big deficits the economy loses some stimulus. Independent observers are skeptical that all three goals can be hit at once. If growth disappoints or deficit reduction falters, debt could actually continue to rise. Ironically, that could raise term premia rather than lower them. Investors would see higher debt and perhaps worry about fiscal sustainability or future inflation, demanding higher yields. In fact, one analysis warns that if the 3-3-3 Plan’s optimistic targets are not met, “significantly larger budget deficits and much higher public debt” would result – and “higher debt [would place] upward pressure on interest rates.” This is essentially the opposite of the plan’s assumption that long-term rates will fall. It underscores a key risk: the plan leans on the hope that bond investors remain confident and term premia stay contained (or even decline), but if investors lose faith, the term premium could jump, making interest costs balloon and undermining the fiscal goals.

So, term premia is a critical swing factor in Bessent’s 3-3-3 Plan. To help ensure rates stay low, the administration has shown interest in influencing Fed policy. We have already seen political pressure on the Federal Reserve to cut rates and “push medium/longer-term rates lower in any way they can”. In late 2024, the Fed did display a bias toward easing (cutting rates by about 1% late in the year) when growth showed signs of cooling, and markets anticipate more of the same in 2025. The administration’s pro-oil, anti-regulation stance is also aimed at containing inflation, which, if successful, would naturally help keep long-term yields down. In summary, the 3-3-3 Plan’s success partially hinges on keeping term premia low. If the Fed and fiscal authorities can engineer a confidence-inspiring mix of fiscal restraint and disinflation, long-term bond investors might cooperate by not demanding much extra premium. If not, the resulting rise in term premia could throw the plan off course by driving up borrowing costs.

Trump’s “Big Beautiful Bill”, Debt, and Term Premia

Alongside the 3-3-3 Plan, another development affecting term premia is President Trump’s flagship fiscal legislation in his second term – often referred to (in Trump’s characteristic phrasing) as a “big, beautiful bill.” While the nickname is lighthearted, the bill itself carries serious implications for U.S. debt. It largely encompasses major tax cuts and possibly spending measures that were promised during the campaign. The result has been a substantial addition to the federal debt. Analysts estimate that the new round of Trump tax cuts costs on the order of $8 trillion over ten years, dwarfing any new revenue from tariffs or other sources. This means that, rather than shrinking, the deficit is likely to remain elevated or even widen in coming years unless offset by major spending cuts (which have yet to materialize in full).

The immediate consequence of this “big beautiful” fiscal push is higher Treasury issuance – the government must borrow more to finance tax cuts and any new spending. When the supply of Treasuries increases, all else equal, investors may demand a higher yield to absorb the additional bonds. In late 2023 and 2024 we got a taste of this: concerns about expanding U.S. deficits and debt helped drive term premia up from historical lows. The term premium on 10-year Treasuries, which had been negative as recently as 2020, climbed back toward zero and above as the market grappled with a “new normal” of larger deficits. The bond market’s so-called “bond vigilantes” – investors who push yields up in response to perceived fiscal irresponsibility – seem to be reawakening. PIMCO noted early in 2024 that forces like a rising trajectory of U.S. debt and the presumable increase in Treasury issuance needed to fund it are signs that term premium could be rebuilt from its ultra-low levels. In other words, high debt and deficits are putting upward pressure on term premia.

To put it simply: more debt = more supply of bonds = potentially higher term premium, especially if investors worry about inflation or creditworthiness. We even saw a credit rating agency (Fitch) downgrade the U.S. in 2023 over fiscal concerns, which contributed to a spike in long-term yields. While the U.S. enjoys “exorbitant privilege” as the world’s reserve currency issuer (meaning it usually can run deficits without immediate bond market panic), that privilege isn’t limitless. If the fiscal path is seen as unsustainable, markets can demand discipline via higher yields, much as they do in other countries. The U.K.’s gilts episode in 2022 (when a fiscally expansive budget caused yields to soar until the policy was reversed) is a cautionary tale noted by many analysts.

From the perspective of our wealth management clients: the new debt from Trump’s big bill could lead to higher long-term interest rates than we otherwise would have had, unless offset by something else. That “something else” could be Federal Reserve action (e.g., cutting rates or even future bond purchases if needed) or the hoped-for growth surge from supply-side policies. Indeed, one rationale behind large tax cuts is to spur investment and growth, which in theory could increase the economy’s capacity and keep inflation low even with stronger demand. If that happened, the Fed might be able to cut rates without stoking inflation, and term premia might not rise too much. However, many economists are skeptical that the tax cuts will pay for themselves or markedly raise potential growth. In fact, as noted earlier, the combination of big tax cuts and only modest offsetting tariffs likely means larger deficits ahead. The Livewire analysis bluntly stated that higher debt from these policies is likely to prop up the neutral interest rate and push rates higher than they would be otherwise.

In summary, Trump’s big fiscal bill is adding to U.S. debt, and this fiscal expansion is a key factor that could drive term premia upward. For investors, that means being prepared for an environment of possibly higher long-term yields, which could pressure bond prices and other asset valuations. For the Fed, it means a trickier balancing act, as we discuss next.

Impact on the Fed’s Dot Plot and Rate Cut Probabilities

The Fed’s “dot plot” – the projection each FOMC member gives for the appropriate policy rate in coming years – encapsulates how the Fed is thinking about the future path of interest rates. As of the March 2025 meeting, the Fed’s median projection indicates that officials still foresee a couple of rate cuts in 2025, but not an aggressive easing. Specifically, the March 2025 dot plot showed the median federal funds rate at 3.9% at end-2025, down from the current range of 4.25–4.50%, implying about 50 basis points of cuts in 2025 (and another ~50 bps in 2026). This was unchanged from the Fed’s outlook in late 2024, signaling a cautious approach. In plain terms, the Fed is penciling in perhaps two quarter-point rate cuts sometime in the second half of 2025.

Why so modest? One reason is that the Fed expects inflation to come down only gradually, partly due to ongoing price pressures like tariffs. Indeed, the Fed’s projection has core PCE inflation still around 2.7% at end-2025, above the 2% target. Until the Fed is confident inflation is durably headed to 2%, it will be reluctant to cut rates too fast. Term premia factor in here because if inflation expectations remain a bit elevated (due to things like tariffs or wage growth), investors may require higher term premia to hold bonds. Fed Chair Jerome Powell noted heightened uncertainty in the outlook, with businesses and households unsure about where the economy is headed. That uncertainty can feed into term premia as well – typically more uncertainty or disagreement among forecasters leads to higher term premium as compensation.

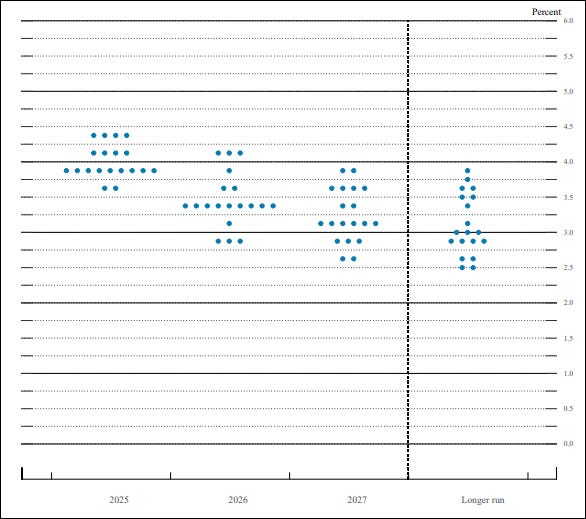

Figure: The Federal Reserve’s “dot plot” as of March 2025 indicates about 50 bps of rate cuts in 2025 (green arrow) and another 50 bps in 2026, after a 100 bp easing in late 2024. Each blue dot represents an official’s forecast for the year-end fed funds rate. (Source: Federal Reserve Summary of Economic Projections, Mar 2025)

It’s worth noting that market expectations for rate cuts have been more aggressive than the Fed’s own dots – a gap that term premia dynamics help explain. In early 2025, financial markets (e.g. futures traders) were betting on the possibility of the Fed starting to cut rates by mid-2025, with the CME FedWatch tool showing odds of a summer cut. This likely reflects investor views that the economy could slow more and that the Fed might respond by easing sooner. Indeed, the first quarter of 2025 saw a slight economic contraction (GDP ticked down at a –0.3% annual rate) even as inflation was still around 3%. This uncomfortable mix of slowing growth and still-elevated inflation – “stagflation” concerns – has made the Fed more cautious. Fed officials like Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic have said they expect maybe only one rate cut in 2025 in their baseline outlook, emphasizing that cutting too soon could risk re-igniting inflation. The Fed is signaling it will not cut rates just because markets or politicians want it, but only if the data (inflation falling, job market weakening) justify it.

Term premia come into play in these deliberations. If investors anticipate that the Fed will have to eventually loosen policy (due to recession risks), they may bid up long-term bond prices now, which lowers long-term yields relative to short-term yields. This expectation-driven effect actually lowers term premia in the near term – a form of the bond market predicting Fed cuts. We saw some of this in late 2024 when recession fears caused a rally in Treasuries and term premia remained very low by historical standards. However, as 2025 progresses, the wildcard is the supply of Treasuries and fiscal outlook. Heavy Treasury issuance to finance deficits could push yields the other way, raising term premia as discussed. The Fed’s dot plot, which currently signals only gentle cuts, implicitly assumes no major financial crisis or deep recession forcing their hand. If term premia were to spike sharply (say, due to a loss of confidence in U.S. fiscal policy or a resurgence of inflation expectations), it might actually tighten financial conditions enough that the Fed would welcome some rate cuts to offset that tightening. In contrast, if term premia stay muted (perhaps because global investors still eagerly buy U.S. bonds, or the inflation outlook improves), the Fed might feel comfortable keeping rates higher for longer, since long-term borrowing costs aren’t restraining the economy too much.

Bottom line: Term premia will be one of the factors influencing the Fed’s future decisions and the evolution of the dot plot. A benign scenario for the Fed would be one in which term premia remain low or only rise gradually – this would keep long-term rates in check and give the Fed breathing room to ease at its preferred pace. A more worrisome scenario is one where term premia jump (long yields rise fast) due to fiscal or inflation concerns; that could either force the Fed to tighten more (if inflation expectations are rising) or conversely to ease sooner (if the higher long rates threaten growth). The interplay is complex, but our eyes are on measures like the yield curve and forward-looking indicators of term premia to gauge which way the wind is blowing.

Outlook: Term Premia and Rate Cut Projections for 2025

Looking ahead, we expect term premia to gradually increase from the rock-bottom levels of recent years, but not explode sharply barring a major shock. The fiscal backdrop – large ongoing deficits and growing debt – will likely put upward pressure on term premia in the medium-term. However, mitigating factors such as a potential economic slowdown, the Fed’s cautious stance, and continued global demand for U.S. Treasuries (especially if other economies face turbulence) could keep a lid on how fast long-term yields climb. In practical terms, this means the 10-year Treasury yield may drift higher relative to short-term rates, but we don’t foresee a return to the extremely high term premia of the 1980s (when inflation was out of control). Even PIMCO’s analysis suggesting a possible return toward a 2% term premium in coming years is a far cry from the 4–5% premiums of forty years ago. A moderate rise in term premia would steepen the yield curve once the Fed begins cutting short-term rates.

On the policy side, our projection for Fed rate cuts in 2025 aligns closely with the Fed’s own guidance: we anticipate the Fed will likely begin cutting rates in late 2025, perhaps by the September FOMC meeting at the earliest, followed by another cut by year-end. In total, about 0.50% (50 basis points) of easing by the end of 2025 is a reasonable base case – for example, two quarter-point cuts bringing the target range down from 4.25–4.50% today to roughly 3.75–4.0%. This is in line with the Fed’s dot plot median (3.9% for end-2025). The rationale is that inflation is expected to slowly grind down toward the low-2% range, and growth is likely to remain subdued (the Fed sees only ~1.7% GDP growth in 2025, and there’s even risk of mild recession). By late 2025, the combination of clearer disinflation and a softer job market should “give the Fed cover” to cut rates modestly, even as they maintain that they won’t relaunch aggressive easing unless absolutely necessary.

It’s important to note that this projection could change if conditions shift. For instance, if the economy slips into a deeper recession earlier than expected (perhaps due to the lagged effects of higher interest costs or a negative shock), the Fed might cut more and sooner – we could envision an accelerated schedule of rate cuts, potentially starting mid-2025, to cushion the downturn. In that scenario, term premia might actually fall initially (as investors flock to bonds on recession fears) before rising later when recovery and huge deficit financing needs re-emerge. Alternatively, if inflation proves stickier – say oil prices spike or tariffs drive prices higher – the Fed could hold off on any cuts until 2026, keeping rates higher for longer. That might cause term premia to rise as bond investors demand more yield if they suspect the Fed will tolerate higher inflation.

Our base case, however, is a middle path: some disinflation aided by the administration’s policies (e.g. increased oil supply helping keep energy prices in check), combined with only partial success in deficit reduction (meaning continued heavy Treasury issuance). This would likely result in the Fed gently lowering rates late next year, while long-term rates don't fall as much because term premia inch up due to the heavy debt supply and fading global liquidity support. By the end of 2025, the yield curve could be either flat or modestly steep (if, for example, fed funds is around 3.75% and the 10-year Treasury yield is perhaps around 4.25–4.5%). Such an outcome would reflect a balance between easing monetary policy and a less favorable fiscal backdrop.

How we made this projection: We base it on a combination of the Fed’s own communications (the dot plot and public comments), current market pricing (investors expect late-2025 cuts, but not an aggressive pace), and the fundamental analysis of term premia discussed above. The Fed’s commitment to data-dependence means they won’t cut until they see clear evidence of a downturn in both inflation and growth. As of mid-2025, they are “sitting on their hands,” resisting political pressure and waiting for more definitive signs of economic deterioration before easing. We anticipate those signs will materialize by year-end. Meanwhile, term premia’s trajectory – rising gradually but not drastically – informs our view that long-term rates will remain somewhat elevated relative to short-term rates. Thus, even as the Fed trims the policy rate, longer-term yields may not fall in tandem; investors should not assume a return to the ultralow mortgage rates or bond yields of the late 2010s.

Portfolio Positioning in a Changing Term Premium Environment:

- In a rising term premia environment, consider shortening bond portfolio duration and rotating into floating-rate or short-term instruments.

- Inflation-linked securities (TIPS) may outperform if rising premia reflects inflation volatility.

- Equities: Growth stocks and long-duration sectors (like tech and utilities) may underperform. Value and financials typically fare better.

- Real assets like commodities and infrastructure may hedge against yield-induced drawdowns.

What Could Go Wrong? The Bond Vigilantes Return: A disorderly rise in term premia could trigger asset re-pricing across markets. If investors collectively demand higher yields due to inflation, deficit growth, or waning Treasury demand, long-end rates may spike. This would tighten financial conditions abruptly, possibly forcing the Fed to react with emergency easing or liquidity injections.

Key Takeaway: Term premia is a vital concept that ties together many threads – fiscal policy, market sentiment, and Fed action. For our clients, understanding term premia helps explain why long-term interest rates move the way they do and what that means for portfolios. In the coming year, we expect a moderate uptick in term premia due to fiscal factors, a cautious but eventually accommodative Fed, and a couple of rate cuts by late 2025 as part of a gradual easing cycle. We will continue to monitor developments – especially any surprises on the inflation or deficit fronts – and adjust our outlook accordingly. By staying informed on term premia and its drivers, we aim to navigate the evolving market landscape and manage the risks and opportunities for your wealth in 2025 and beyond.

Sources:

· Bernanke, Ben S. “Why Are Interest Rates So Low? Part 4: Term Premiums.” Brookings Institution (2015)

· UMB Bank Capital Markets Division. “Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent’s 3-3-3 Plan and the Path Forward.” UMB Blog (Mar. 17, 2025)

· Davies, Kieran. “Wishful Thinking: The Trump Administration’s ‘3-3-3’ Economic Plan.” Livewire Markets (Feb. 13, 2025)

· Roche, Cullen. “Three Things I Think: 3–3–3 Edition.” Discipline Funds (Nov. 25, 2024)

· PIMCO (Seidner & Dhawan). “Back to the Future: Term Premium Poised to Rise Again...” (Feb. 2024)

· Federal Reserve, Summary of Economic Projections (Mar. 19, 2025); Bondsavvy summary of March 2025 Fed Dot Plot

· Fidelity Viewpoints (Kana Norimoto). “When Will the Fed Cut Interest Rates?” (May 7, 2025)